The Basics of Avalanche Slope Assessment - A Process

M. Trehearne 2022 - Climbers nearly hit by a combination windslab and serac avalanche on the Ramp Route, Mount Athabasca. Jasper National Park, Canada.

HOW TO ASSESS AVALANCHE SLOPES - THE BASICS

We're all likely going to end up at some point. Following an often enthusiastic, very well intentioned partner(s) up an uptrack, into some seemingly monsterous place, tentative and uncertain, lingering in the back of the group, staring upwards into what looks like the gates to oblivion. What in the hell exactly it is that we've gotten ourselves into.

One of the biggest challenges our Guides observe in training this skill set with our students, is an ability to create simplicity in an assessment process. Given how much there is to take in and process with respect to avalanche slopes, a common outcome is that critical observations best viewed in isolation, often become conflated or mixed, reducing our ability to focus on the essential inputs required in the moment or circumstances, before bringing them togeather in balance to make a high quality slope assessment.

The intention here is to help provide those who might find it of use, some insight into the processes our Guides use most commonly in assessing and teaching avalanche slope assessment. The desire being to share the processes that we find create more objectivity, and more clarity when we need it most. For us this represents a process that has been tested, refined, debated, torn down and built back up and it's value reflected back to us by our students in form of their own observable progression, and the the value and confidence it creates for them.

We hope you find it of use.

1.

DON'T CONFLATE TERRAIN AND SNOWPACK

The single most common cause of errors or challenges in avalanche slope assessment we see in our students initially come from a yet un-learned ability to separate the assessments of terrain and snowpack. Conflating these two, commonly causes confusion, and reduces clarity in the critical observations required for both. For an avalanche to take place, specific terrain characteristics are required. Learn these. If the terrain characteristics are not such that they will produce, ie: allow an avalanche to happen, than we almost never waste any time as Guides thinking about the snowpack or its problems, grounding ourselves in the knowledge that the terrain cannot produce.

So, our first tip is this:

Tip #1 - In your minds eye, separate terrain, and the snowpack sitting on top of it. We always consider terrain in isolation, before making any assessments of the snowpack.

More on all the specific terrain characteristics to consider below.

2.

Assessing snowpack problems

Generally, we tend to feel that only after assessing the terrain in isolation, and concluding it has the required characteristics to produce an avalanche, is it time to assess the snowpack problems which might be present on the slope you're looking at. These are most frequently communicated to us in the Public Avalanche Bulletin (www.avalanche.ca).

We'll dive into this more deeply in the following, but in the meantime, here's our second tip:

Tip #2 - If you believe the terrain can produce, overlay the snowpack and its problems into the terrain and consider then how exposed you want to be to the hazard, or if zero exposure is prefered.

UNDERSTANDING HOW TO INTERPRET AVALANCHE PROBLEMS FROM AVALANCHE.CA + OVERLAY THOSE PROBLEMS ON A SLOPE

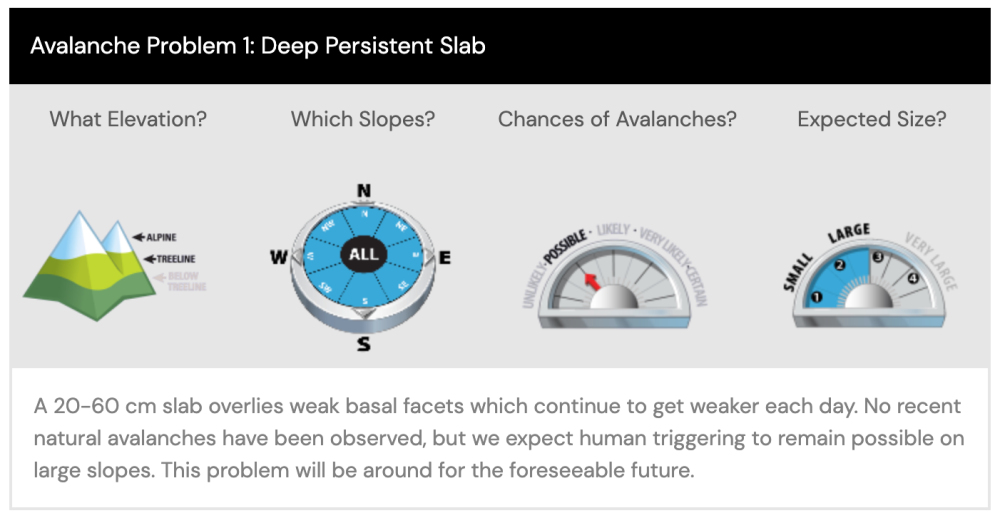

Our ability to apply snowpack problems to the terrain we've assessed and deem capable of producing requires an understanding where the problem or hazard lives, it's home in the terrain, or; where it resides prior to an avalanche occuring. To do this we need to understand primarily the first two forecast points:

Elevation Band

+

Aspect

If we use the info from the example shown, is tells us:

- There is a "Deep Persistent Slab" Problem which can produce avalanches.

- The avalanche problem exists at Treeline, and in the Alpine.

- The avalanche problem exists on all aspects.

So, with respect to snowpack problems, you can assume that if you're looking at a slope that is in either the alpine or at treeline, and has the terrain characteristics to produce, the slope is home to the above mentioned avalanche problem / hazard. Go ahead and assume the problem lives there. The last consideration becomes creating an understanding of our risk, exposure and vulnerability as ski tourers, splitboarders, or snowshoers which we'll talk about next.

Is it avalanche terrain or not?

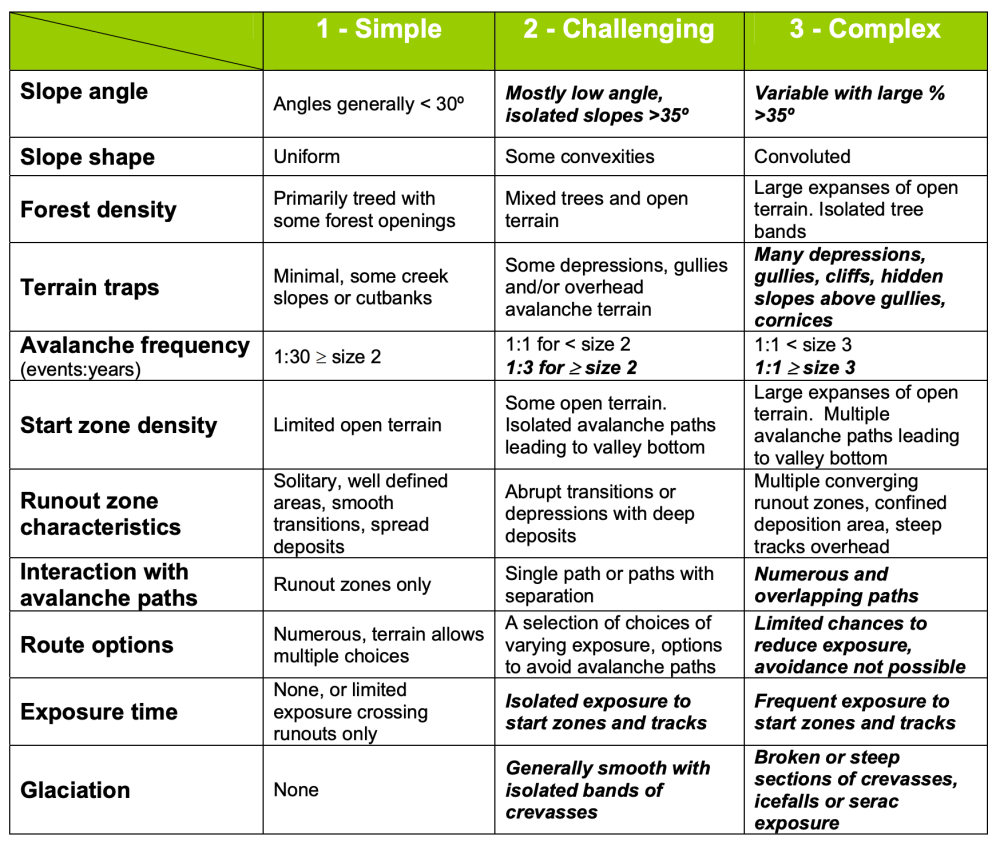

Do designate terrain as capable of producing an avalanche, ie: avalanche terrain, (not even thinking about snowpack problems yet) we generally fall back on what you'll see taught as a primary support structure for decision making on our AST1 & AST2 Courses;

The ATES Technical Model.

One of the single biggest factors that would indicate a slope being qualified as avalanche terrain is slope angle. Ie: how steep is the slope.

Typically, slopes less than 28˚ will not produce avalanches. That said, there's certainly a number of our Guides who have seen 25˚ slopes produce. Therefore, if you are not exposed to 25˚ or steeper terrain, you're likely not in avalanche terrain. Anything steeper than 28˚ however you can assume will produce, with most slab avalanches occurring between 28˚ and 48˚, and loose snow avalanches becoming most frequent when steeper than 45˚.

With a slope angle that tells us we're looking at avalanche terrain, other inputs in the ATES Technical Model, give us basis for more in depth assessment of the slope. These additional terrain parameters often don't on their own confirm a slope as avalanche terrain, however they do influence the likelihood of triggering, and/or increase the potential consequences of an avalanche occuring.